Pain is often the first warning sign of rhizarthrosis.

You might first notice it when performing simple everyday tasks – turning a key, opening a jar, writing – and it tends to develop gradually, sometimes without you being immediately aware of what is causing it.

Rhizarthrosis is localised at the base of the thumb, but it can also radiate into the wrist or forearm, giving the impression of diffuse or referred pain. These sensations often vary from day to day and can be confusing and worrying.

But where does the pain come from? Is it just caused by cartilage wear? Why do some people suffer from stiffness or pain at night, while other people only experience discomfort when they overuse their thumbs? Understanding the link between rhizarthrosis and joint pain helps to improve identification of the signs, anticipate progression of the condition and adopt the right hand movements.

This page follows on from and elaborates on ‘Understanding rhizarthrosis’, which details the mechanisms of the condition, its initial symptoms and the various stages.

Pain associated with joint wear

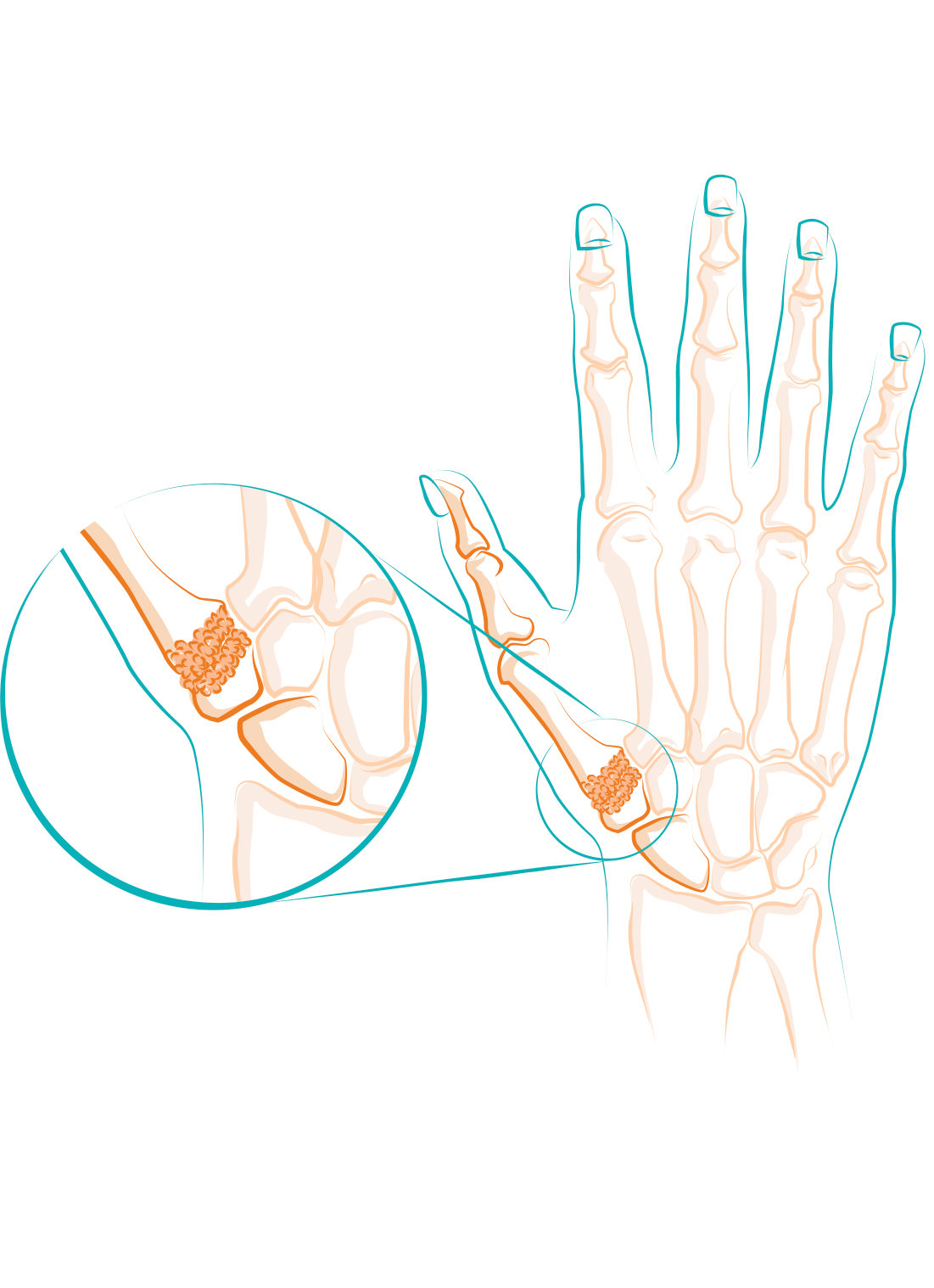

Rhizarthrosis is a form of arthritis that affects the trapeziometacarpal joint at the base of the thumb.

It belongs to a type of arthritis known as ‘primary’ (or idiopathic) osteoarthritis, the exact cause of which is not always known. Progressive cartilage wear leads to joint imbalance, resulting in mechanical stress, inflammation, and eventually pain.

As the cartilage gradually wears down: the bones rub against one another, the synovial membrane may become inflamed, the ligaments stretch, the muscles around the joint start to weaken.

This process makes certain hand movements, tasks and activities particularly painful, especially if they involve pinching objects between the thumb and index finger or thumb opposition. Unscrewing a cap or cork on a bottle, holding a telephone, doing the buttons up on a shirt… – these are just some of the tasks that can become uncomfortable or even impossible.

If you want to map out the progress of the condition, the page ‘Stages of rhizarthrosis progression’ provides concrete reference points.

Fluctuating pain

Rhizarthrosis-sufferers find that the pain is not always present. It often features inflammatory flare-ups interspersed with calmer phases. There are therefore a number of different pain profiles:

When discomfort sets in, you can use protective measures to limit strain on the joint.

You will find useful advice if you click on ‘Everyday hand movements, tasks and activities to adapt’ and ‘Self-massaging your thumb’.

Localised pain, that can sometimes spread

Even though rhizarthrosis only affects the thumb joint, you may experience diffuse pain. There are various reasons for this:

It is not uncommon for other joints to be affected, for instance the joints in the fingers or wrist. This sometimes makes it difficult to pin down the origin of the pain.

It is a good idea to consult a doctor to review the situation. The most common tests and examinations performed can be found under ‘Diagnosis of rhizarthrosis‘.

Distinguishing rhizarthrosis from other conditions

Some forms of thumb pain may indicate rhizarthrosis, but may not actually be due to that. If in doubt, other potential causes should be taken into consideration. These can include:

The link between joint pain and rhizarthrosis is based on a set of clinical indicators. A healthcare professional is best placed to interpret the signs and direct you towards an appropriate treatment.

You can find further details under ‘First symptoms of rhizarthrosis’.

How to relieve day-to-day pain?

Pain is not inevitable. There are a number of things you can do to avoid it or alleviate it, depending on the level of joint damage:

Remember:

Rhizarthrosis often causes joint pain, but the form, intensity and location of that joint pain may vary. If you can learn to distinguish between them, action can be taken earlier, you can avoid certain constraints and you can preserve your quality of life.